| vaticancatholic.com - English Channel |

Faith & Doctrine | History | Traditional Catholic Issues Bro. Peter Dimond In this video I want to cover some important examples of catechisms published after key sessions of the Council of Trent which affirm the true position that the Sacrament of Baptism is necessary for salvation without exception, based on Catholic dogma and the words of Jesus in John 3:5. These points are very significant because opponents of Catholic truth on baptism frequently mispresent or outright lie about the facts and the Tradition on this issue.

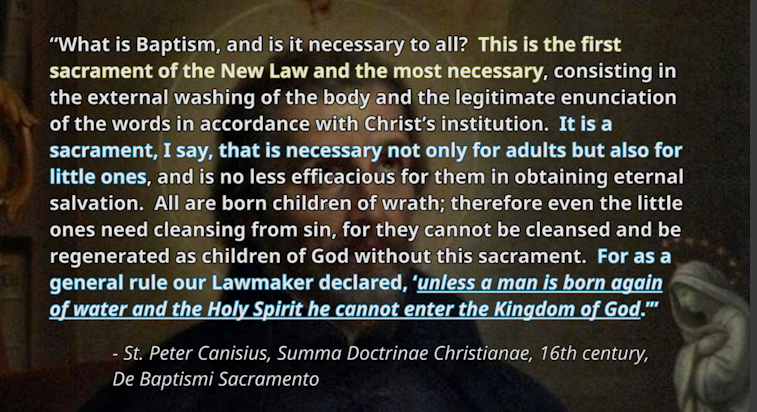

St. Peter Canisius, who was born in the Netherlands in 1521, is a Doctor of the Catholic Church. During his life he corresponded with various popes, including Popes Pius IV, St. Pius V, and Gregory XIII. Canisius was a delegate to the Council of Trent and attended the Council as a theologian. The Catholic Encyclopedia notes at Trent he “spoke twice in the congregation of the theologians. After this he spent several months under the direction of St. Ignatius” (O. Braunsberger, “Blessed Peter Canisius”, The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1911). In 1555 St. Peter Canisius published his Summa Doctrinae Christianae, which is known as his greater or larger catechism. This catechism became world-famous. It was translated into 15 languages during his lifetime, and by 1686 it had gone through 400 editions. In 1583 it was printed and published in Slovenian in Rome at the command of Pope Gregory XIII. The Catholic Encyclopedia states that “It remained the foundation and pattern for the catechisms printed later.” In Pope Leo XIII’s Aug. 1, 1897, encyclical Militantis Ecclesiae, he praises St. Peter Canisius’ Summa or greater catechism. He says that it’s “written in beautiful Latin and not unworthy of the Fathers of the Church. This remarkable work was enthusiastically received by learned men in almost all the countries of Europe.” In this world-famous catechism and theological work by St. Peter Canisius, a Doctor of the Church who attended the Council of Trent as a theologian, there is an entire section on baptism and its necessity. In the catechism St. Peter does not teach ‘baptism of desire’ or ‘baptism of blood’, even though he had plenty of opportunity to do so in this rather large work. On the contrary, he teaches that the Sacrament of Baptism is necessary for all without exception and that unless man is born again of water and the Holy Spirit he cannot enter the Kingdom of God. He also references passages from Church fathers which specifically teach that unbaptized catechumens cannot be forgiven or saved without water baptism. He bases his teaching on baptism on key passages in the Council Trent, John 3:5, etc. He even references Sess. 6, Chap. 4 of Trent, and Sess. 7, canon 5 of Trent, as we will see. Here’s what his catechism says.

Now there are some extremely important points about this passage, including the footnotes. St. Peter Canisius teaches that no one can be saved without being born again of water and the Holy Spirit based the words of Jesus in John 3:5. These words of Our Lord are in fact a dogma taught by the Catholic Church in both the Councils of Florence and Trent. Those who reject and condemn the position that everyone must be baptized to be saved (which includes almost all priests, even so-called traditional ones, at this time of the Great Apostasy) are rejecting and condemning the words of Jesus Christ which have been declared as a dogma without exception by the Catholic Church. Indeed, in this passage of the Catechism St. Peter Canisius gives a footnote to Trent’s dogmatic statement in Sess. 5 on Original Sin. That session of Trent declared the words of Our Lord in John 3:5 are a divinely revealed truth without qualification.

St. Peter’s Catechism likewise teaches that the Sacrament is necessary for both adults and children without exception. Now, the word necessary in Latin and in English typically means ‘required, essential or unavoidable.’ In context necessity can be qualified. Someone could qualify necessity by speaking about a necessity of a certain kind or for a certain group or a necessity of precept or by noting exceptions in context. But when something is said to be ‘necessary’ or ‘of necessity’ without qualification or exception, especially in a dogmatic decree, that means that’s absolutely required, essential, and unavoidable. To bolster this point, consider how the Council of Trent used the word necessitate in canon 2 on the Sacrament of Baptism. The canon states:

Does the word ‘necessary’ or ‘necessity’ here mean: 1) water is absolutely necessary/unavoidable for the sacrament to take place? Or does it mean: 2) water is necessary in most cases, but in exceptional circumstances one could receive the sacrament of Baptism without water? Clearly it means #1 and it excludes #2; for you can never, in any circumstance, receive the Sacrament of Baptism without real and natural water, as even ‘baptism of desire’ advocates admit. Their position is that someone can be saved without receiving the Sacrament, but they acknowledge that the Sacrament can never occur or be received without actual water, without a person baptizing, etc. So, when Trent defines that real and natural water is de necessitate (of necessity) or necessary for the Sacrament of Baptism, that means that water is absolutely necessary, essential, unavoidable in all cases and circumstances for the sacrament to occur. It follows, therefore, that when, just a few canons later, Trent defines without qualification that the Sacrament of Baptism itself is necessary for salvation, that means that it’s absolutely required for salvation in all instances without exception.

So, just as canon 2 does not admit of exceptions to what is considered necessary, the same is true of canon 5. Moreover, and this is important, Trent’s teaching on this matter is not limited to declaring that the Sacrament is necessary for salvation. We saw that in Sess. 5 on Original Sin it infallibly declared that unless a man is born again of water and the Holy Spirit he cannot enter the Kingdom of God. That language doesn’t use the word necessary, and it infallibly teaches that no one can be saved without water baptism based on the words of the Lord. The Council of Florence taught the same truth. In his Catechism, St. Peter Canisius likewise teaches that the Sacrament is necessary for adults and children without exception and he cites John 3:5. IMPORTANT FOOTNOTES

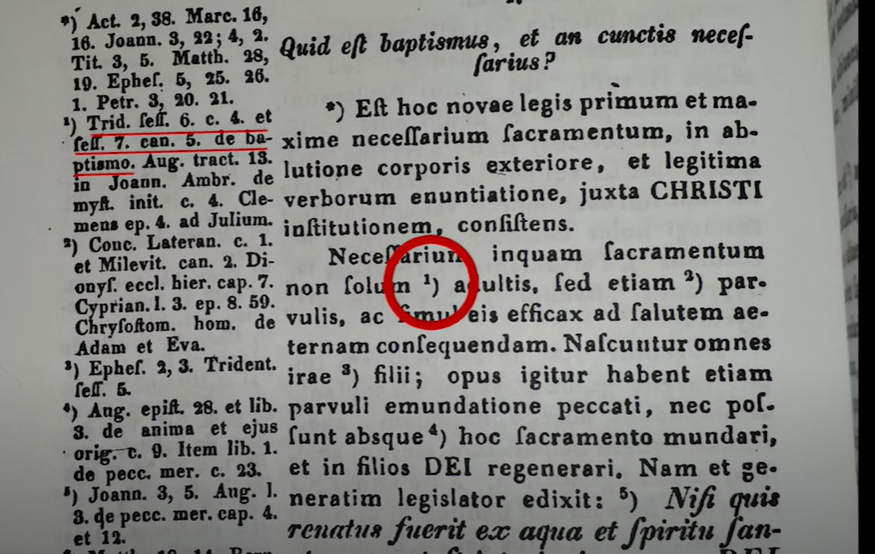

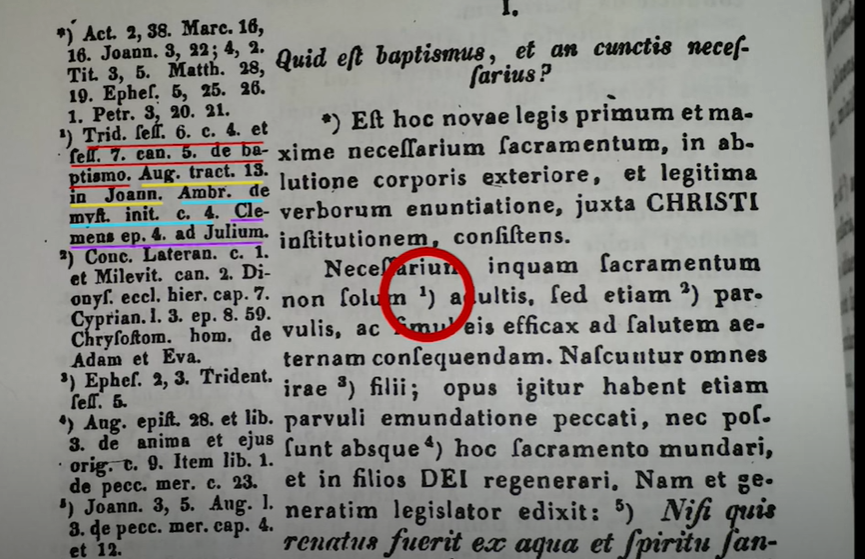

Now, what’s fascinating is that his footnote #1, which appears after the words “not only” (or non solum in Latin), is to Sess. 6, Chap. 4 of the Council of Trent and Sess. 7, Can. 5. We just cited Sess. 7, Canon 5. St. Peter Canisius references this crucial canon as a basis for his teaching that the Sacrament is necessary for all without exception. But the first reference he gives is to Sess. 6, Chap. 4.

Those who are familiar with this issue know that Sess. 6, Chap. 4 of Trent is the passage that many ‘baptism of desire’ advocates wrongly think taught baptism of desire, but it didn’t at all. We demonstrate that in our material. See our video called The Council Of Trent Did Not Teach “Baptism Of Desire”; but briefly: Sess. 6, Chap. 4 of Trent says that justification cannot take place without ‘sine’ the laver of regeneration or without a desire for it, as it is written John 3:5. Logically and contextually, that does not mean that one can be justified by the desire for baptism in the absence of baptism. When considering this issue, it’s important to note that the word ‘without’ should be distributed in English examples to properly translate the passage and understand the point, because in the Latin the word ‘sine’ (meaning without) grammatically applies to both lavacro (laver) and voto (vow or desire). Sine is a preposition that takes the ablative case, and in Sess. 6, Chap. 4 both lavacro and voto are in the ablative case. Hence, the word ‘without’ applies to both’. So, in English the passage should read: cannot take place without or without, as it is written John 3:5. Now, to say that something cannot take place without x or without y logically means that if either x or y is missing, that thing cannot take place. It does not mean that one is sufficient in the absence of the other. Thus, to say that justification cannot take place without the laver of regeneration or without a desire for it logically means that if either the laver of regeneration or a desire for it is missing, justification cannot take place. That’s our position; it’s not the position of those who support ‘baptism of desire’. And the very same sentence of Trent concludes by affirming John 3:5 as it is written (sicut scriptum est), which confirms the point and contradicts the idea of baptism of desire. Baptism of desire posits that John 3:5 is not to be understood as it is written. It advances exceptions to John 3:5, which is not the teaching of Trent. Logically, contextually and considered with the rest of Trent and Catholic dogma, Sess. 6, Chap. 4 is demonstrated to not teach baptism of desire, but to affirm the words of Jesus in John 3:5 just as they are written. Some have tried to respond to this argument by claiming that if this were true, it would require that infants desire baptism, but we refute that by pointing out that the passage concerns the justification of the impious (impii). The word impii in Latin cannot apply to people who do not have the use of reason, as we showed in our other video/article on Trent. Sess. 6, Chap. 4 is about adult justification. A desire for baptism is a prerequisite for adult justification. Thus, in the case of adults, if either the desire for baptism or water baptism is lacking, justification cannot occur, as it is written John 3:5. Now, St. Peter Canisius, who attended the council of Trent as a theologian, bolsters all of our points on this passage by specifically referencing it in the process of teaching that no one can be saved without water baptism. He also cites it directly in reference to how adults require the sacrament, which supports the fact that the passage is about adult justification, not about infant justification. His citation of Sess. 6, Chap. 4, in the very passage of his catechism on the necessity of the Sacrament, constitutes a post-Trent interpretation of Sess. 6, Chap. 4, by a doctor of the Church and a theologian who attended the Council that’s perfectly consistent with (and in fact supportive of) our position on this and indeed of the Church’s true position on this matter. It’s a providential and powerful vindication. St. Peter Canisius was perhaps the most widely-read author of all the theologians who attended Trent. In fact, his interpretation of Sess. 6, Chap. 4, which was first published in the mid-1500s (the definitive edition of his catechism being considered the 1566 edition, with earlier editions having been published in the previous decade), was one of the earliest (if not the earliest) commentary on this matter to have been published after the key sessions of Trent. And, as we’ve just shown, his official teaching based on this and other passages was that no one can be saved without water baptism. That’s not the position of those who believe in baptism of desire.

Now, in further support of these points, the other three references given in his footnote 1, after the references to Sess. 6, Chap. 4 and Session 7, Canon 5 of Trent, are to St. Augustine, St. Ambrose and a passage that had been attributed to Clement. All three of the passages he cites teach that unbaptized catechumens cannot be regenerated unless they actually receive water baptism. They directly contradict the idea of baptism of desire. The first passage from St. Augustine states:

That’s the kind of passage from the Church fathers that you’d see in an anti-baptism of desire publication, for it expresses the truth that no matter how much progress an unbaptized catechumen makes he cannot be forgiven and saved unless he is baptized. The next passage St. Peter cites is from St. Ambrose on the Mysteries, to the same effect:

That also contradicts the idea of baptism of desire, and in the full passage St. Ambrose teaches that the water, the blood and Spirit are all necessary to receive the baptismal effect, a truth was infallibly taught by Pope St. Leo the Great (as our material covers). So, St. Peter Canisius cites these passages, which are clearly against the concept that an unbaptized catechumen can be justified and saved without water baptism, along with Sess. 6, Chap. 4 of Trent and Sess. 7, Can. 5 of Trent, to teach that adults must receive water baptism to be saved. It’s a striking vindication of our position. In the same Catechism, in his section 19 Concerning faith and the symbol of the faith, he speaks about the remission of sins. He says:

Once again we see this doctor of the Church, who attended the Council of Trent, teaching that no one can receive the remission of sins or be saved without faith and baptism. In his catechism St. Peter Canisius also very strongly teaches that no one can be saved without the Catholic faith, even those who die ignorant of the essential truths. He teaches that outside the Church there is no salvation for mortals but certain destruction, including for Jews and pagans “who never received the faith”.

This dogma, that the Catholic faith is necessary for all, is rejected by almost all so-called traditionalist priests in our day. Now that we’ve covered that St. Peter Canisius’s catechism favors our position, let’s look at two other post-Trent catechisms. REV. JAMES BUTLER’S IRISH CATECHISM In 1775 Rev. James Butler, Bishop of Cashel Ireland, published his famous Irish Catechism. It was approved by the four archbishops of Ireland and used as the general catechism in Ireland. It was also approved by the First Council of Quebec and authorized as the official English catechism for the Archdiocese of Toronto in 1871. In this catechism we find the same truth on baptism taught (and the false ideas of baptism of desire and blood are not taught).

This what we find in all dogmatic and magisterial pronouncements on the issue. It is the true rule of faith on this matter. Note also that this catechism understands necessary to mean that “without it one cannot be saved.” The same catechism also teaches that people above the age of reason must know the essential truths of the Christian faith, such as the Trinity and the Incarnation. This Catholic teaching, as we mentioned, is rejected by almost all so-called priests and so-called traditionalist priests in our day, who believe that people in false religions can be saved.

Among the five mysteries that must be known by those who have the use of reason, the Catechism mentions: 1) That there is one God; 2) the Trinity; 3) the Incarnation; 4) the Crucifixion, Death, and Resurrection of Jesus Christ; and 5) that God rewards good and punishes evil.

THE PENNY CATECHISM Another example of a catechism that properly transmitted the Church’s true teaching and rule of faith on this matter during this period is the Catechism of Christian Doctrine or the Penny Catechism. It was used as the standard catechetical text in Great Britain throughout most of the 20th century. It states:

No exceptions are given. So, those are just a few examples of catechisms published after the Council of Trent that properly transmitted the Church’s rule of faith and true teaching on this issue. Certain errors did creep into many other catechisms, however, as our material covers in detail. But most importantly, throughout this whole period the Church’s official teaching continued to uphold the true rule of faith: that no one can be saved without baptism and the Catholic faith. We see this, for example, in encyclicals to the entire Church right up to Vatican II. Copyright © 2022 Most Holy Family Monastery |

Post-Trent Catechism By St. Peter Canisius Contradicts “Baptism Of Desire”

March 15, 2022

SHOW MORE